Q: You describe the book as a family, but it’s obviously very concerned with individuals also.

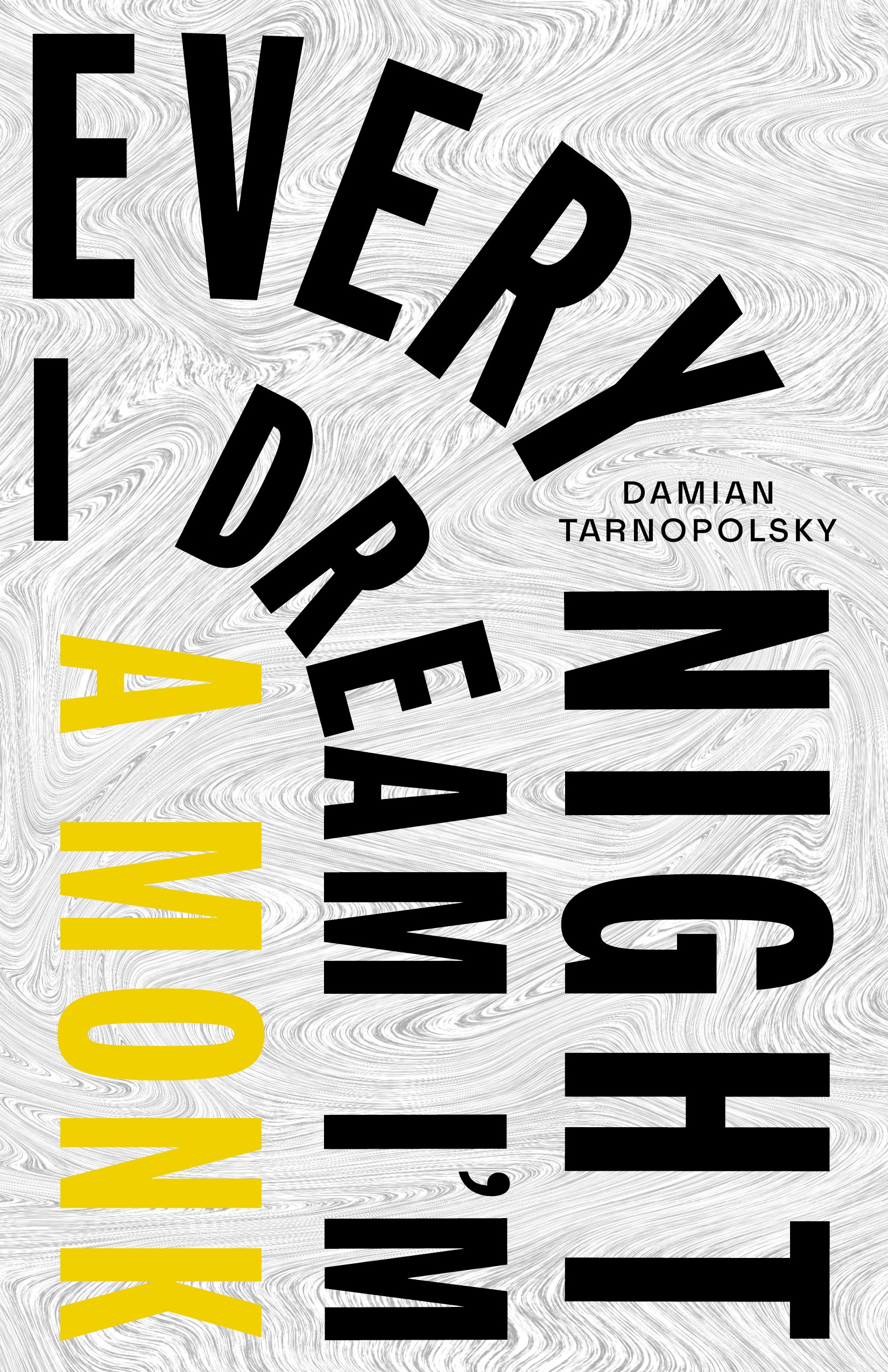

Fair point. While I was writing it I got a little obsessed with ideas about the self: what does it mean to be the same person over time, or not? How fragile and temporary is our sense of self? What do we owe our future selves, how do we relate to our past selves? It’s such a simple thing, that no one talks about much, but it started to seem like a puzzle and a scandal and in part the book is a response to it (while also reflecting my own changes over time: many of these stories are quite old, some of them are brand new). I have so many inarticulate thoughts about this, but they make their way into the book as characters, questions, themes. Is Mark in the book a little trapped by stories he’s telling himself about himself? Why can’t he get free of them? We identify often with our conscious minds, but aren’t we much more than that in our memory and desire, our physical presence, our dreams? And how much of our sense of self actually comes from our connections to the people around us? What happens when they get frayed? A rich internal life can be a blessing, but often, paradoxically, we often feel most ourselves when least conscious, in moments of great passion or awe, I mean at our most animalistic or most transcendent: Every Night I Dream I’m a Monk, Every Night I Dream I’m a Monster.

Q: But there’s some (if I may say) dark, sad, nasty material in the book. Why don’t you write about nice things?

A friend of mine says he can only write at 5am, and that what he writes has to make sense to his 5am self—not his “proper” daytime, 11am self, with its friends and obligations, but the secret self that wants and despairs and hopes and lingers. There’s a lot to that. But I hope that there’s some joy in the stories too, that formally, sentence-by-sentence, though it might seem dark, it’s actually full of love and care. That it’s paying attention and giving sympathy to partial people in difficult moments, I was going to say people who are doing their best, but no, we don’t always do our best, do we? Sometimes we can’t. I hope the book successfully stages the ranting and violence and hate that that suffering can lead to, rather than monochromatically endorsing it. But it’s up to the reader to judge, of course.

Q: You teach in a Narrative-Based Medicine program. What is that, and how does it relate to your fiction?

Part of what I teach is called “narrative competence,” which is encouraging health practitioners to get better at handling stories (their own, their patients’), at being reflective about their place in a certain plot, about the particular words they’re using. And realizing that stories have more agency here than we sometimes realize. Recently the work has given me community, colleagues, stability, and connection that I’ve never had before, and the students are incredibly devoted, thoughtful, hard-working people. It’s very rewarding to spend time with them. It’s hard to teach people to write, really, but I try to show them where some of the interesting stuff is, what some useful questions to ask are, what drawers the tools are in, and how best to use them, and it seems to help them, much of the time, which is satisfying too. I can’t phone it in because the material and the subject matters to me. I don’t know if it’s had a massive impact on my writing, but (cliché approaching) you do learn a lot from teaching, from having to find ways to talk about what you do every day and how you do it. Though as Doris Lessing said, “To write you have to be slightly bored,” and so I have to be quite disciplined about protecting writing time, making sure I have time to be bored.